Life Sciences Emerges As Investment Sweet Spot In Softening Office Market

Life Sciences Emerges As Investment Sweet Spot In Softening Office Market

Record-breaking years of growth in Canada’s life-sciences sector has turbocharged the demand for laboratory real estate in an acutely undersupplied market.

These market fundamentals have attracted the attention of investors, who, prior to 2020, had no real presence in a class of real estate traditionally owned by universities and hospitals.

“It’s definitely the hot asset to be chasing right now,” says Robin Buntain, a principal at Avison Young’s Vancouver office, specializing in sales and leasing.

“The investor community wants to diversify away from the softening office market,” he says. Lab and medical manufacturing real estate – national vacancy for which “is basically zero” – is the new “sweet spot for investors. It’s fascinating how quickly this has happened.”

Now, nearly 5.4 million square feet of purpose-built lab space is proposed or expected to be delivered across three Canadian cities by 2027, according to a new report by commercial real estate firm JLL.

While Toronto dominates the life-sciences market in Canada in terms of existing building inventory, “Vancouver leads in future supply – with more than double the amount of new space in the works compared to Toronto,” says Scott Figler, JLL’s national research manager for capital markets in Canada.

Driven by technological leaps in areas such as personalized health care, regenerative medicine, genomics and synthetic biology, not to mention a global pandemic that ushered in historic levels of funding for some companies, “Vancouver has seen the most life-sciences job growth in Canada,” says Mr. Figler. “The city has seen more than 7,000 new jobs in the past 10 years, compared to Toronto, which has added around 3,000.”

Vancouver’s planned 2.9 million square feet of lab space nearly equals its entire existing market.

About 80 per cent of this development – spearheaded by some of the most prominent names in the industry, including Beedie, PC Urban and Westbank – will be located in the burgeoning Innovation District, just south of the downtown core.

Mr. Figler says optimism about the wave of new supply in Vancouver as well as across the country comes with caveats.

It is currently “far more expensive” for developers to lock in financing and build than it was a year ago, owing to rising interest rates and lofty construction costs, he says.

Lab space, he adds, can be the most costly of all real estate classes to construct because buildings typically require at least double the structural frame strength, compared to offices, in order to support lab equipment weight and to eliminate vibrations which could ruin sensitive experiments.

Ceilings must be at least 14.6 feet high (compared with the office industry standard of 10 feet) to accommodate large equipment, such as autoclaves and cold storage, and its ventilation – and more power is required to run it. (Standard research facilities can draw triple the watts per square foot compared to computer-filled office space, according to Stanford University’s Laboratory Standards and Design Guidelines.) In addition, backup generators are essential in case of power outage.

“A lot of times you can tell by looking at satellite images and the HVAC [heating, ventilation and air conditioning] system on top of a building – if it looks really souped up, that’s a good indication that it’s a lab building,” says Mr. Figler.

Elevated development costs and a tenant pool comprised in part by unproven biotech startups, can make investment risky, he says.

To thrive, investors and developers “have to think like scientists,” he adds.

“Developers who are successful aren’t just projecting costs and revenues,” he explains. “They have in-house scientific understanding; they understand what the tenants are working on and are able to assess the probability of, say, a certain gene therapy getting clinical trial approval or another round of venture capital funding.”

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/EFKBI2MKVFC4FBOTDCAUOFG2VU.jpg)

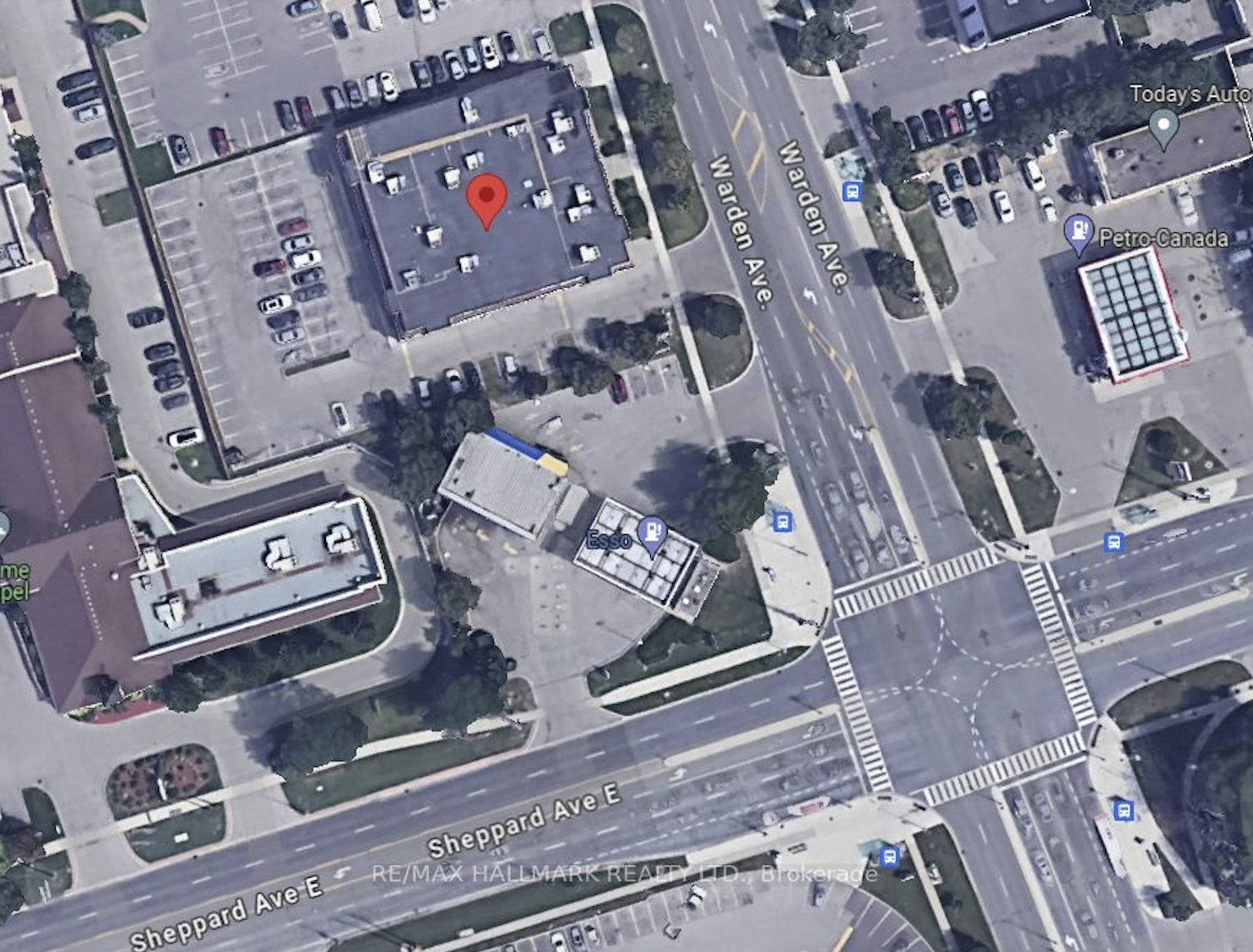

In the centre of Montreal’s university and life sciences ecosystem, Jadco Corporation’s upcoming Inspire Bio Innovations aims to accommodate pharmaceutical and biotech companies.JADCO CORPORATION

For Montreal developer Jadco Corporation’s first life-sciences complex in the city’s downtown core, called Inspire Bio Innovations, the 35-year-old company partnered with anchor tenant, global clinical research firm CellCarta, for phase one of the project. Then it hired CellCarta’s senior vice-president to manage the next two phases of the $350-million, 450,000-square-foot state-of-the-art laboratory.

“At CellCarta, I became an expert in facility systems,” while supervising lab development in many countries, says Normand Rivard, managing partner of life sciences and innovation at Jadco.

“There’s nothing more precious than a blood sample from a patient with a rare disease,” he says. The building and the mechanicals to protect it are crucial and “Jadco takes that very seriously.

“We want to build the best facility with everything that a biotech or pharma company needs to perform their delicate and critical operations.”

With completion for the centre set for late 2027, no tenants have yet signed on.

“But there’s already very high level of interest,” says Mr. Rivard. “We’re confident we’re going to fill the building in a flash.”

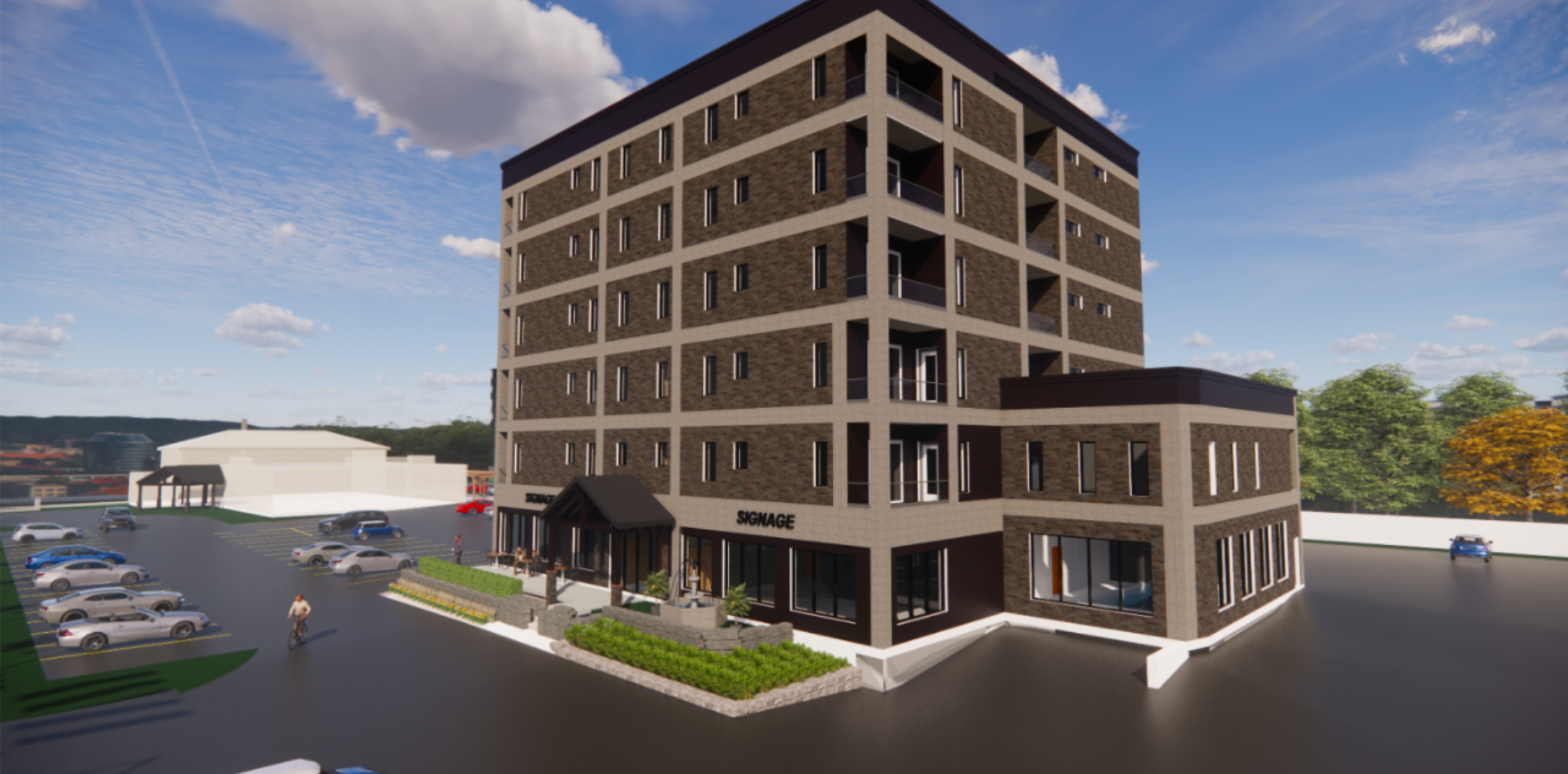

In Vancouver, Low Tide Properties, which already operates five life-sciences buildings, calls itself the city’s largest landlord in the life-sciences space. The company, which also owns multifamily properties, is set to add another eight-storey, 218,000-square-foot life-sciences building, Lab 29, in the Innovation District.

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/ZXSCSC37QNBFFKRC5573WWWADY.jpg)

Vancouver’s Low Tide Properties bills Lab 29 as a “cutting-edge laboratory and office building” that will add to its collection of bio sciences facilities.LOW TIDE PROPERTIES

Low Tide views itself as “a partner” for tenants, says Adam Mitchell, vice-president of asset management and development.

It’s critical that the infrastructure at those buildings is working flawlessly so tenants don’t have an interruption during a major experiment, says Mr. Mitchell.

“Our building operators have specialty training in running a life sciences building,” he says. “We’ve also had good staff continuity, so they’ve been able to hone those skills and make sure that they’re adding a value to the property.”